- Jerome Cholet

- All Artworks

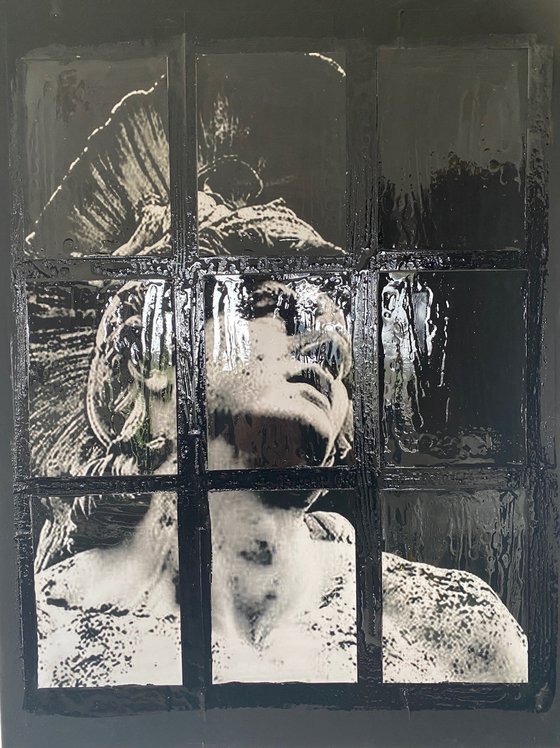

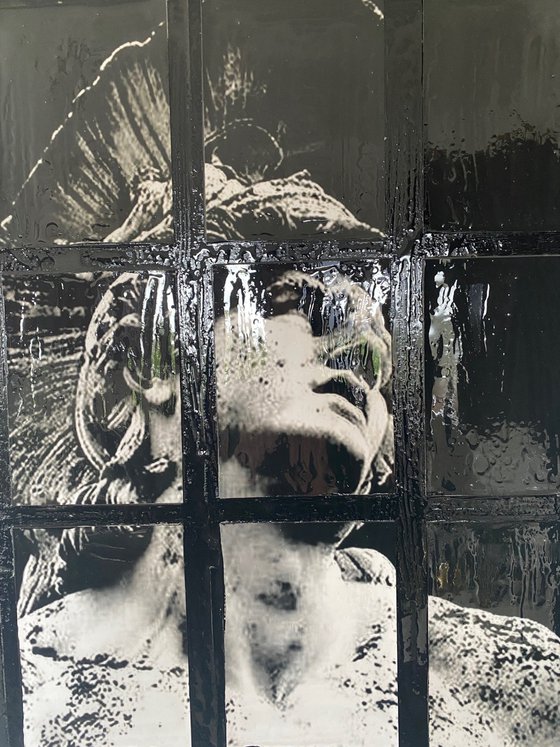

- Dying Achilles Black

Dying Achilles Black (2025)Spray paint painting by Jerome Cholet

50 x 70 x 0.5cm (unframed)

£435.68

Original artwork description

There are artworks that depict myth. And then there are artworks that resurrect it.

Jérôme Cholet’s “Achilles Black” is not a mere homage to classical heroism. It’s a resurrection—visceral, erotic, devastating. Sourced from Ernst Herter’s 1884 sculpture “Dying Achilles”, nestled in the imperial gardens of Empress Sisi’s palace in Corfu, Cholet drags the marble warrior out of history and into the throbbing now.

The collage is composed of nine photographic fragments, reassembled like shards of a broken mirror. The surface is washed in glossy black spray paint and sealed in a pool of epoxy resin so thick, it feels almost like flesh. The result? Something between relic and fetish object.

Achilles, in his final breath, rendered in stark black and white, is no longer a marble corpse but a wounded god of sex and sorrow. His neck, exposed. His lips, parted. His musculature, caught in the throes of beautiful failure. The glossy resin coating traps the image beneath like a relic under glass—untouchable and yet screaming to be touched.

This is death as performance, vulnerability as power. In an age of curated masculinity and ironic distance, Achilles Black is shamelessly sincere. It dares to make mythology erotic again. It’s as if Robert Mapplethorpe had a séance with Caravaggio and invited Jenny Saville to handle the bodywork.

Cholet is doing what few contemporary artists dare: mixing high classical iconography with a raw, queer sensuality. Where Kehinde Wiley monumentalizes his subjects in oil and grandeur, Cholet dissects and deconstructs, turning heroism into intimacy.

The tragedy of Achilles—invulnerable but for his heel—becomes a metaphor for modern man: armored in aesthetics, undone by a single soft spot. And that soft spot has never looked so desirable.

Collectors take note: “Achilles Black” isn’t just a piece for the wall—it’s a mirror for the psyche. It’s the ultimate must-have for those unafraid of beauty, ruin, and resurrection.

Materials used:

Photo, Paper, Spray Paint, Epoxy resin

Details:

- Spray paint painting on Canvas

- One of a kind artwork

- Size: 50 x 70 x 0.5cm (unframed)

- Ready to hang

- Signed on the back

- Style: Collage

- Subject: Nudes and erotic

Tags:

#water#sculpture#gay#war#greek#lgbt#mythology#ares#achilles#mythologie14 day money back guaranteeLearn more

Original artwork description

There are artworks that depict myth. And then there are artworks that resurrect it.

Jérôme Cholet’s “Achilles Black” is not a mere homage to classical heroism. It’s a resurrection—visceral, erotic, devastating. Sourced from Ernst Herter’s 1884 sculpture “Dying Achilles”, nestled in the imperial gardens of Empress Sisi’s palace in Corfu, Cholet drags the marble warrior out of history and into the throbbing now.

The collage is composed of nine photographic fragments, reassembled like shards of a broken mirror. The surface is washed in glossy black spray paint and sealed in a pool of epoxy resin so thick, it feels almost like flesh. The result? Something between relic and fetish object.

Achilles, in his final breath, rendered in stark black and white, is no longer a marble corpse but a wounded god of sex and sorrow. His neck, exposed. His lips, parted. His musculature, caught in the throes of beautiful failure. The glossy resin coating traps the image beneath like a relic under glass—untouchable and yet screaming to be touched.

This is death as performance, vulnerability as power. In an age of curated masculinity and ironic distance, Achilles Black is shamelessly sincere. It dares to make mythology erotic again. It’s as if Robert Mapplethorpe had a séance with Caravaggio and invited Jenny Saville to handle the bodywork.

Cholet is doing what few contemporary artists dare: mixing high classical iconography with a raw, queer sensuality. Where Kehinde Wiley monumentalizes his subjects in oil and grandeur, Cholet dissects and deconstructs, turning heroism into intimacy.

The tragedy of Achilles—invulnerable but for his heel—becomes a metaphor for modern man: armored in aesthetics, undone by a single soft spot. And that soft spot has never looked so desirable.

Collectors take note: “Achilles Black” isn’t just a piece for the wall—it’s a mirror for the psyche. It’s the ultimate must-have for those unafraid of beauty, ruin, and resurrection.

Materials used:

Photo, Paper, Spray Paint, Epoxy resin

Details:

- Spray paint painting on Canvas

- One of a kind artwork

- Size: 50 x 70 x 0.5cm (unframed)

- Ready to hang

- Signed on the back

- Style: Collage

- Subject: Nudes and erotic

Tags:

#water#sculpture#gay#war#greek#lgbt#mythology#ares#achilles#mythologie